Most fungi are beneficial or harmless, but a few will cause serious health issues in your chickens.

Fungi comprise a kingdom of organisms that include molds, mildews, yeasts, and mushrooms. These related organisms share the following characteristics:

- They have a nucleus, or core.

- They lack chlorophyll and thus are unable to produce their own food, but instead absorb nutrients from other organisms, living or dead.

- They are made up of either long branching filaments or, as in yeast, single cells.

- They have a cell wall made of chitin — the same substance that makes up an insect’s shell.

- They all reproduce by means of spores.

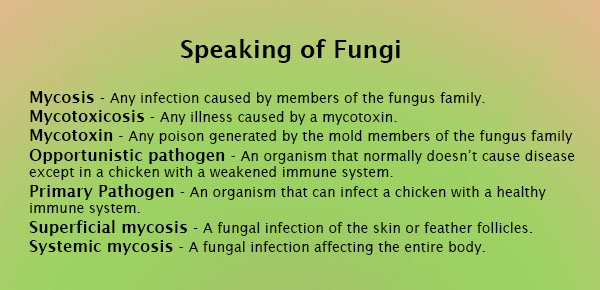

The word “fungus” comes directly from the Latin word fungus, meaning “mushroom.” The study of fungi is called mycology, from the Greek word mykes, meaning “mushroom.”

Of the one-million-plus different species of fungi, most are either beneficial or harmless. Some, however, generate powerful poisons in the course of their normal metabolism, while others are parasites capable of invading a chicken’s skin or internal organs.

Mycotoxicoses

Mycotoxicoses are caused by various kinds of mold that grow in grain and release toxins as part of their normal metabolic processes. These toxins can poison chickens in much the same way that pesticides do. Such illnesses nearly always result from eating moldy feed, although some toxins can poison chickens through skin contact or by being inhaled, but they do not spread directly from chicken to chicken.

The molds that produce mycotoxins grow naturally in grains, and some molds generate more than one kind of poison. But not all molds produce mycotoxins, and not all mycotoxins are poisonous to chickens. Penicillin, for instance, is a mycotoxin that poisons bacteria, so instead of calling it a toxin, we call it an antibiotic.

The severity of illness caused by mold toxins and the specific signs depend on the type of mold involved and how long the chickens are exposed to it. Their age and state of health also influence the degree of poisoning. Conversely, fungal poisoning can increase a chicken’s susceptibility to other diseases.

Diagnosing Mold Poisoning

Molds are natural environmental contaminants that are commonly present in grains, but they cannot produce toxins unless conditions are favorable for their growth. Even then, mycotoxins are usually at such low levels that they remain undetected and rarely cause serious illness in chickens. Diagnosing an illness caused by a specific mycotoxin can prove difficult for these several reasons:

- Signs may not become readily apparent unless the chickens consume or inhale a toxin over a period of time.

- Not all mycotoxins produce readily identifiable signs of illness.

- Many mycotoxins produce signs that are similar to one another

- or to signs of other diseases.

- Mold is not always easy to detect in contaminated feed or litter,

- which may look and smell perfectly normal.

- Many mycotoxins remain stable during feed milling and storage, leaving active toxins after the molds that produced them have been destroyed.

- More than one toxin may be involved, resulting in a confusion of signs.

- Mycotoxicosis is not so common that it is the first thing anyone thinks of when chickens fall ill.

- Infectious diseases, internal parasites, and other stressors increase a chicken’s susceptibility to fungal poisoning, which then may not be recognized or identified as contributing to the chicken’s condition.

- Most mycotoxins increase a chicken’s susceptibility to infectious diseases, which may be diagnosed without identifying mold poisoning as the underlying cause.

- Methods of analyzing feed or litter for mycotoxins are not always readily available to the backyard chicken keeper.

- By the time signs appear, the mold-contaminated feed or litter may have been used up or replaced, making a positive identification of a toxin impossible.

- Chickens that are not exposed to a lethal dose of toxin tend to recover on their own once the contaminated feed or litter is removed.

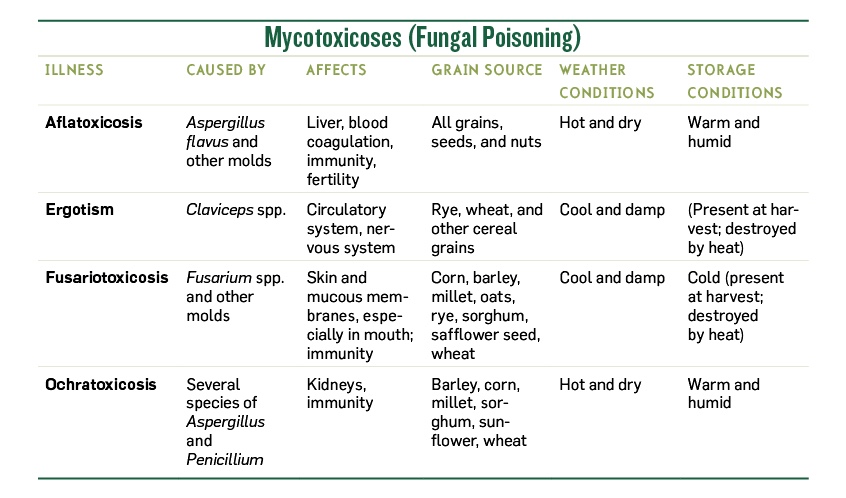

- Suspect mycotoxicosis if chickens die with few, if any, signs of illness and you cannot determine the cause, especially if your chickens have been eating feed from other than the usual source. Of the many different mycotoxins, three groups are the most likely to affect backyard chickens: aflatoxins, fusariotoxins, and ochratoxins. A fourth mycotoxin, ergotism, can poison chickens foraging on cropland or wild grasses.

Aflatoxicosis

The most common mycotoxins affecting chickens and other poultry, aflatoxins were discovered in the 1960s, when thousands of turkeys died after eating contaminated peanut meal. Aflatoxins consist of four distinct poisonous compounds produced by Aspergillus flavus and other molds that readily contaminate feedstuffs grown in hot, dry weather; stored with a moisture content greater than 14 percent; or stored under humid conditions or for too long.

Aflatoxicosis is the resulting illness. How sick the chickens become depends on their age, how much contaminated feed they eat, and how long they eat it. Young chickens are more susceptible than older birds but are much less susceptible than ducklings or turkey poults.

Signs of Aflatoxicosis

Aflatoxins are highly toxic, and acute aflatoxicosis is deadly. Signs of acute toxicity include loose droppings containing undigested seed or grain particles, pale comb and wattles, low egg production with reduced fertility and low hatchability, incoordination and paralysis, followed by a high death rate.

Chronic aflatoxicosis increases a bird’s susceptibility to heat stress and infection, reduces egg production, and causes significant liver damage, which can lead to ascites. Although aflatoxins are known to cause cancer in humans, chickens have a shorter lifespan and rarely develop this type of tumor.

Preventing Aflatoxicosis

Aflatoxins are not stored in the chicken’s body but are rapidly excreted in bile and urates. Replacing contaminated feed can therefore result in the rapid recovery of chickens that are not lethally poisoned.

These molds get into grain with the help of insects that attack growing or stored crops and break down the protective hull of individual kernels, opening the way to mold penetration. Grains that are deliberately cracked or crushed to make them easier for chickens to digest, when stored improperly or for too long, are also subject to mold contamination.

To avoid aflatoxicosis, do not feed your chickens grains or seeds that are visibly infested with insects or that show signs of insect damage — such as the presence of fine powder or kernels that are off-color, smaller than normal, or misshapen. Most commercially prepared pellets and crumbles contain mold inhibitors that prevent the development of aflatoxins. Sprinkling diatomaceous earth into fresh scratch grains helps inhibit insects.

Excerpted from The Chicken Health Handbook© by Gail Damerow. Used with permission from Storey Publishing.